As reported by The Guardian last month, suicide rates among students in England and Wales have risen slightly over the past 10 years, with 1,330 student deaths by suicide – 1,109 (83 percent) were those of students studying at undergraduate level, while those studying at postgraduate level accounted for 221 deaths (17 percent).

The Guardian also reported that, according to the Office of National Statistics (ONS), the year leading up to July 2017 saw a total of 95 student deaths by suicide – which equates to one every four days.

Additionally, of the 1,330 deaths, there was a significant gender disparity - 878 (66 percent) were men, and 452 (34 percent) were women. But why are the majority of student suicides male? Read on to discover the reasons behind this gender gap and what needs to change.

What is happening?

Earlier this summer, an article by The Tab mentioned that 11 students from Bristol University killed themselves in the last 18 months – and just over half (six) of them were males.

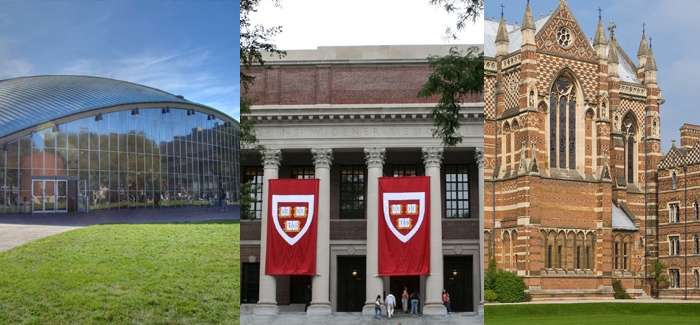

As is the case with the overwhelming amount of suicides across some of the UK’s top universities in the last 10 years, including Oxford and Cambridge, the epidemic has led people to question Bristol University’s ability to provide adequate support to students suffering with mental health issues. Very few of the deaths are being reported by the media, and parents of those who died are calling for more to be done to help students who are suffering.

In a 2017 BBC Three documentary titled ‘Real Stories: Student Suicide’, it was revealed that ‘one third of students report feeling depressed or lonely’ while ‘nearly half of students with a mental health condition do not disclose it to their universities’ – both facts may point to an ongoing pattern concerning a lack in open communication between students and their universities.

The documentary highlighted three cases of student suicides, of which two were male students.

Why are suicide rates higher among males than females?

A commonly raised argument for this is the notion that men, in general, tend to be more prone to ‘bottling their feelings’ because of the stigmas society has always attached to men who are ‘too overt’ with their emotions. According to George E Murphy in an article titled ‘Why women are less likely than men to commit suicide’, “Men value independence and decisiveness, and they regard acknowledging a need for help as weakness and avoid it”, while “women value interdependence, and they consult friends and readily accept help”. As the statistics continue to show, this idea may prove to be true, and some of the reported behavioral patterns displayed by men prior to their suicides seem to testify to that.

Andrew Kirkman, who was a 20-year-old Physics and Philosophy student at Oxford University, died in 2013 after he took his own life by “gassing himself” inside a tent.

Student Suicide documented Andrew’s friends and family, four years later, as they publicly shared their perspectives following his death, including his final days leading up to it. His girlfriend Clarissa, who lives in Brazil, made a revealing statement that could very well attest to the societal stigmas surrounding masculinity and mental health: “He told me that he felt like a fake and that he was falling short of the image that people had of him.” She added that “He didn’t want to tell anyone else about his depression because he felt ashamed” and that “He told me that he really, really wanted to die and he didn’t even know anymore (sic) if he wanted to get better”.

The documentary also revealed the final days of Stefan James Osgood, a 21-year-old mathematics student at Aberystwyth University, who died in March of 2016 after self-inflicted injuries. His distressed mother gave a candid interview, speaking of her son’s final days and expressing that he was “tired of his depressions (sic) and tired of carrying them and holding them and not showing anybody”. She also claimed that Stefan had a “fear of failure” and that “he just didn’t want to be a burden”. Ms Osgood thinks that “Stefan was very much of the mindset that it wouldn’t be very ‘blokey or ‘manly’ or appropriate to admit that you’re depressed”.

Ged Flynn, CEO of the young suicide prevention charity PAPYRUS, told TopUniversities that he thinks the high number of suicide among men in contrast to women may be the result of more than just one particular factor: “Whilst it used to be the case that males used more lethal means, that is no longer necessarily true. I think the reasons for these demographics are more complex than this.”

Some things need to change…

Among the concerns in relation to the often-reported inadequate support when it comes to students’ mental health, is the law regarding data privacy.

As reported by the BBC, Bristol student Ben Murray was the 10th to die in Bristol University’s sweep of suicides, and his father, James Murray, gave an interview to the BBC earlier this year as he voiced his concerns about the tight data protection rules which currently give people over 18 the right to decide to withhold certain confidential information – even if that means from their own parents or next of kin.

In the interview, Mr Murray said that even though the university had “been very open” with Ben’s family since his death, they adhered to the data privacy rules while he was a student there, an act his father expressed discontent towards: “Having gone through all the different moments when we could have intervened to save our son’s life, it’s absolute nonsense that you would look at an issue and say: ‘You’re an adult therefore data privacy applies.' Data privacy that may cause the vulnerable to lose their lives makes no sense at all.”

As a response, the university issued a statement saying that they will be considering an “opt-in contract with students”, which will ensure the accessibility of contact with a nominated next of kin, should a “major concern about their wellbeing” arise.

PAPYRUS’ Ged Flynn did not comment on this particular case, but upholds the belief that “we need to shift from data protection to data sharing when it comes to protecting life”, affirming that, “PAPYRUS is very clear: when life is in danger, information should be shared safely with others in order to protect it. There is no excuse for professionals to hide behind privacy and confidentiality when there is a clear presentation of suicidal risk or emotional distress”.

Flynn went on to suggest that “At the very least, professionals should engage with the person they deem to be at risk and ask them how they would like to communicate with others to keep them safe”, adding that “Very often, a person at risk of suicide longs for this connectivity and support from others”.

“Suicide stigma prevails”

However, the data protection law might not be the sole factor partially to blame for the perturbing number of young suicides in the UK. As Ged Flynn states, we also need to change the language we use around the topic of suicide - “Using the phrase ‘commit suicide’ is an anachronism. We commit crimes. Suicide is not a crime in this country nor has it been since 1961. If we use language that belongs to the world of crime, no wonder that stigma prevails and prevents young people and others from acknowledging, let alone sharing thoughts of suicide and seeking help”.

In addition, many people with suicidal thoughts are often described as being outwardly rather calm and collected – which, to professionals, often makes the acts of self-harm and suicide a lot more difficult to prevent. Dr Chris Kenyon, a local GP to whom Andrew Kirkman was referred by his tutor shortly before his death, mentioned that the Oxford student’s “demeanor was neutral and pleasant” and that “he was not visibly distressed”, adding that “he didn’t give much away (emotionally) at all.” He also made a profound revelation: “We always ask people about self-harm thoughts – and I did with Andrew, he said he had some fleeting thoughts but would never act on them”.

When asked about Andrew’s case, Flynn expressed that although he “cannot comment on the particular case”, he emphasizes the importance of shifting the thought patterns around, and the behaviors towards suicide: “Over the years, we have learned more about how suicidal ideation often presents itself. Many people who are at risk mask the reality.”

“Suicide stigma prevails. That means many people who experience thoughts of suicide learn quickly to adapt their behavior and modify it so that others will have no idea what is going on for them.”

Moreover, Flynn reaffirms the reality that “It is too hard, often, for a person who is experiencing thoughts of suicide to speak out about them”, confirming that “This is often because of social stigma and taboo. We need to change this as a matter of urgency”.

The importance of dialogue and communication

It is no secret that, along with utilizing the correct type of language, an open dialogue plays a crucial role in unlocking many of society’s dilemmas. Suicide prevention is no different, and the charity PAPYRUS is a firm believer in this: “PAPYRUS is simply trying to encourage universities not to hide away from using safe language around suicide, not to hide the word suicide in the dialogue with and about students”, says Flynn, stating that “Stigma still is all pervasive and we need to change that.” He also suggests a change in the nature of the communication between professionals and vulnerable individuals: “Rather than expecting those who are experiencing thoughts of suicide to reach out, we encourage everyone to learn how to reach in, to ask about students' well-being, to express concern if they see changes in behavior, to ask if suicide is on the cards.”

Flynn concludes: “The most prevalent myth is that, by asking about suicide we put the idea into another person’s head. This is nonsense and all the evidence suggests that this is not the case.

“That almost 100 students have taken their own lives for most years over the last couple of decades means that we must be ever vigilant and learn from previous deaths, to prevent future tragedies.”

If you or anyone you know has been affected by any of the issues raised in this article, please don’t suffer in silence – contact Papyrus for help and support (pat@papyrus-uk.org, 0800 068 41 41)